After an embarrassingly long hiatus, let's see if I remember how to do this…we'll begin with Kyra's arrival, back on March 11. (Kyra is a good friend of ours from Homer who decided to come down to give the people of Bluefields a lesson in beekeeping, and to spend some time with us.)

Pat and I arrived in Managua early, and so spent a couple hours waiting at the restaurant of the Best Western hotel, conveniently located directly across the street from the airport. This decision cost us $35 in food and drinks—an outrageous sum anywhere outside this little isla of Gringolandia. Fortunately, Kyra arrived on time and in tact, schlepping two ancient army duffle bags primarily full of—yep—hats. We spent the night at Norma's, an old friend of Edwin's family (and godmother of Milagro), then returned to the airport the next morning to catch a small plane to Bluefields. If you're unsure of where exactly Bluefields is located, and don't have your atlas handy, just run an imaginary line due east completely across the country, until you hit the Atlantic Ocean, and you will find Bluefields. The name comes from the Anglicization of Bloefeldt, the Dutch captain who first decided it looked like a good place to be. It is populated by a variety of races and ethnic groups, including the Miskito and several other groups of Indians, decedents of African slaves, British traders and sailors, and Mestizos, any mix of Spanish and indigenous blood. English is one of the dominant languages, although it's spoken with a distinct patois that takes some getting used to. The majority speak Spanish as well, along with Miskito and various other indigenous languages. The main thing I noticed was that no one seemed the least bit interested in us—and I mean that in a good way. In Rivas, we always stand out, especially women. So it is pretty much a given that after I leave the house, and before I arrive at my destination, I will have been greeted, shouted at, whistled at, hooted at, complimented, proposed to, insulted, and airily kissed—even when Pat is with me. But in Bluefields, Kyra and I were invisible, and it was lovely. This is not to say the people were in the least unfriendly. On the contrary, everyone we met was warm and welcoming, even after learning we were neither missionaries nor wealthy tourists.

The plane ride took just over an hour, and allowed us to see the island Omotepe from a radically different perspective. And then, after 45 minutes or so of geometrically splattered farms and fairly rugged terrain, the Atlantic appeared, brilliant and vast and somehow very different from the Pacific just a couple hundred miles away. Bluefields itself appeared to sprawl across the hills, around a large curving bay, bright and colorful even from the air. We were met by Luvianis (known as Luvi), and a cousin, making us a party of five plus a driver, all of whom were expected to fit into one of the tiny, ubiquitous Hyundai taxis that careen through the narrow crowded streets at alarming rates. We were deposited on a corner, alongside a sign reading "Do Not Throw Garbage Here", precariously balanced atop a substantial mound of….garbage. From there, the road became a narrow concrete path, meandering its way down and down, between closely built houses and shacks, snaking its way jaggedly amidst barbed wire fences and sturdy white pickets, before at last terminating at a large wooden gate. Beyond the gate: Luvi's family's place. Theirs is not a large lot, but it is right on the water. Their house, a simple wooden box, sits partially on solid ground, partially on stilts above the rocks and waves. A boardwalk runs the length of the house, continuing past the cozy bungalow Pablo, Luvi's father, built for Brad and Ruth, the missionary couple who spends alternate months down there, primarily working with local children. They had kindly invited us to stay in their place as it was their month to be in Costa Rica.

While Kyra and I settled in, Pat immediately made himself useful helping Pablo and his crew offload several dozen freshly caught nurse sharks from the panga, a 35' long open fiberglass boat, used by everyone, for everything throughout Central America. Pablo is one of Bluefields most successful fishermen, boasting a solid reputation for quality and reliability in a very competitive market. The nurse sharks are valued not only for their solid, flavorful meat, but to a greater extent for their fins, which are sold to the Chinese for upwards of $25/lb. Pablo also fishes for assorted other local fish, such as snook (robalo) and snapper, but the real money is in lobster, and it was on that subject he approached Pat on the third or fourth day of our stay, once it had been established we all liked each other. At present, he goes for lobster the traditional way: with oxygen tanks and crooked rods. He does very well like this, but his catch is understandably limited. His plan is simple: traps. 200 of them eventually (he can take around 12-15 per trip in the panga). And since any trap marked with a buoy would immediately be pulled by the unscrupulous, he would need to drop the markers at least 30' below the surface, requiring a GPS with a mapping function to locate them. He has proposed that in exchange for advancing him the funds he needs to purchase the GPS and materials to build the traps, he will pay us back a percentage of every haul, plus 10%. Ideally, he needs around $4000 to make this happen. Obviously, this is a wee bit beyond our means. Pat suggested he start with perhaps 50 traps and see how it goes. We are awaiting his reply.

And then it was bee time. Kyra had come prepared to show the willing how to build bee-boxes, how to find actual bees to populate the boxes, and how to harvest the honey. She got to do all of these, although her only student turned out to be Monje, Pablo's father. But he was a very, very good student. First on the agenda was locating some willing bees. Monje had done his research, and had found three possibilities: 1) in a hole in the ground, 2) in an abandoned piece of machinery, and 3) in someone's roof. Kyra opted for the hole in the ground first, and was pleasantly surprised to find a colony of very docile bees a foot or so below the surface. We returned to Pablo's to begin construction of a bee box, assisted by Monje, Pablo, Santos, one of Pablo's cousins, and Bruno, a decrepit old nutter who complained constantly and expected financial compensation for every action—invited or no. Monje kept him in check for the most part, and I silenced him for a while by giving him a loaf of coconut bread. This band of brothers, under Kyra's guidance, constructed a very respectable bee box, which we then loaded onto the panga and ferried to the general vicinity of the hive. Once on site, Kyra began smoking out the bees, fearlessly sticking her face into the hive, along with her hand and most of her arm. Before long, she was removing honeycomb panels, which she showed Monje and Bruno how to tie to the new bee box, a move which would encourage the bees to make the move voluntarily. After an hour or so, when over a dozen panels had been removed and reattached in their new location, she reached the conclusion that this was a dying hive: it had no queen. But she told them to leave the new hive and to check on it from time to time; it was always possible that a swarm would find it and take it over.

Option 2, the machinery, was rejected as unsuitable, leaving us to tromp over to option 3,

a rooftop infestation. The house, a large, modern place, was owned by a couple who work on cruise ships, and was being cared for by the woman's uncle, a large black man with a nearly impenetrable accent, making his Spanish easier to understand than his English. He was very kind, and grateful that we (well, Kyra) had come to help rid him of the incessant buzzing and regular stings his unwelcome guests contributed. As it turned out, nearly a quarter of the sizeable roof was a massive hive, and from the number of dripping combs Kyra pulled out, a very active one as well. Night fell quickly, so we left it for the following morning—a mistake, as it turned out. While we spent our evening being dressed up in foolish disco clothes and dragged to Bluefields premiere dance hotspot, a second swarm had become aroused by the activity, and declared war. When we arrived just after sunup, the sky above the house was blackened by tens of thousands of very distraught bees. Kyra donned her protective gear, lit up the pile of dried grass she had been using for smoke, and jumped into the fray. Bees were plummeting down on us, staggering drunkenly around our feet, and shooting off in all directions. After about an hour, Kyra located the queen—a large, blond, and according to Kyra, very fecund beastie. Just as Kyra had her lightly grasped in her fist, she burst out and disappeared into the jungle. Kyra was devastated; after all that time and effort, to have trapped the queen would have secured the success of the new hive (the boys had built a second box), as well as eliminated the hive from the roof. There is a considerable chance that the queen will return to her clan, and finding the box there, make it her new home. Monje promised to check back frequently and keep us posted.

Between all the bee activity, we did get to see some of the area. Felipa, Luvi's mother, lead us around one morning, on a tour of the city itself. It has the feeling of the old West, with closely packed wooden building, and no shortage of saloon-style watering holes. And while reggae is popular, Hank Williams rules, at least when he's not drowned out by hiphop. We got to try coconut bread, which isn't remotely coconutty, but is still delicious. And we were fed 'rondon', a local specialty made with coconut milk and whatever else is handy; picture a sort of Thai soup, without the curry. The family piled us into the panga and took us first to see their farm, several hundred acres about an hour's ride up an estuary. The land is undeveloped now, but they have big plans—including a bee operation. And finally, just hours before boarding the plane home, we got to see the Atlantic Ocean, walk the beach, splash in the waves. It was the first day of Semana Santa (Holy Week), so there were small thatched-roof restaurants and bars set up, each blasting its particular genre of music. We chose one, ordered some beers and sodas, and relaxed, feeling it was well-deserved after the bee-frenzied days we'd endured.

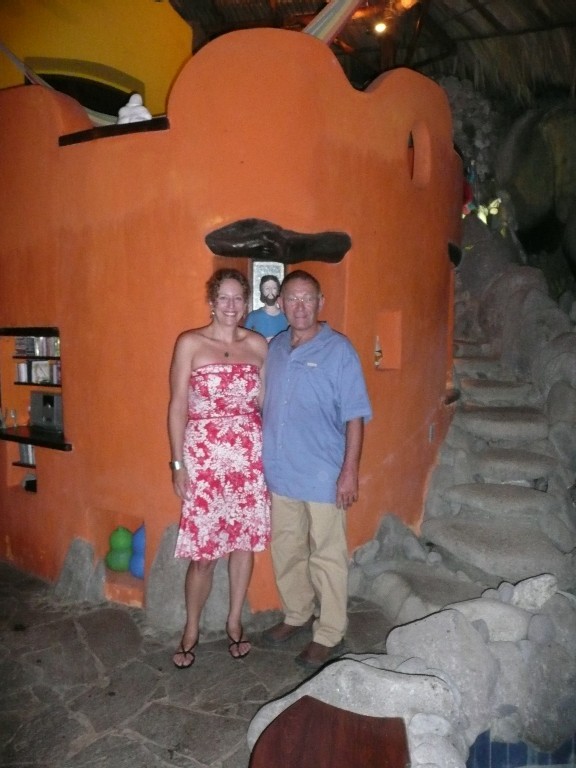

Once back from Bluefields, things didn't slow down much. We took Kyra to Granada and Laguna de Apoyo, then finally back to Buenos Aires, in time for Semana Santa. We spent a lot of time out at our house, on the beach, hanging with local friends, playing with all the kids. On the last Sunday of the week, Edwin's family and some friends took us to Marsella, an amazingly uncrowded but very beautiful beach on the Pacific. We found a little thatched beach hut to shield us from the blazing sun, and spent the day swimming in both the ocean, with its crashing waves, and a nearby estuary, flat and calm, and ideal for the kids. We distributed hats (in Bluefields, too, we passed out some, and left around 40 with Pablo and Felipa, to give out to the families in the area, and the kids Brad and Ruth work with), took lots of pictures, ate too much, drank too much, and generally celebrated Holy Week like native Nicas. Towards the end of her stay, we took our bikes across to Ometepe Island, and nearly killed ourselves peddling halfway around the island in the heat of the day—poor planning on our part due to time constraints—something you should never have when traveling in Nicaragua. We spent Kyra's last night back up in Managua, this time at Christina's (Edwin's cousin's) house. They took us to a traditional Nica restaurant, where Kyra ordered a mixed plate and was presented with enough food for a small village, including blood sausage, twice-fried plantain slices, spicy sausage, grilled pork chunks, fried pork fat, and hunks of salty but tasty cheese. She impressed everyone by polishing off more than half—the rest was packed up for Pat for his trip home the next day. And for her final adventure, after I was on my way to visit friends and family on a 7am flight, as Pat drove her to the airport a few hours later, they were pulled over for an imaginary violation ("You ran a red light." "It was yellow." "You're still supposed to stop." Sure.), which cost three times the going rate to get out of—a fat $18.

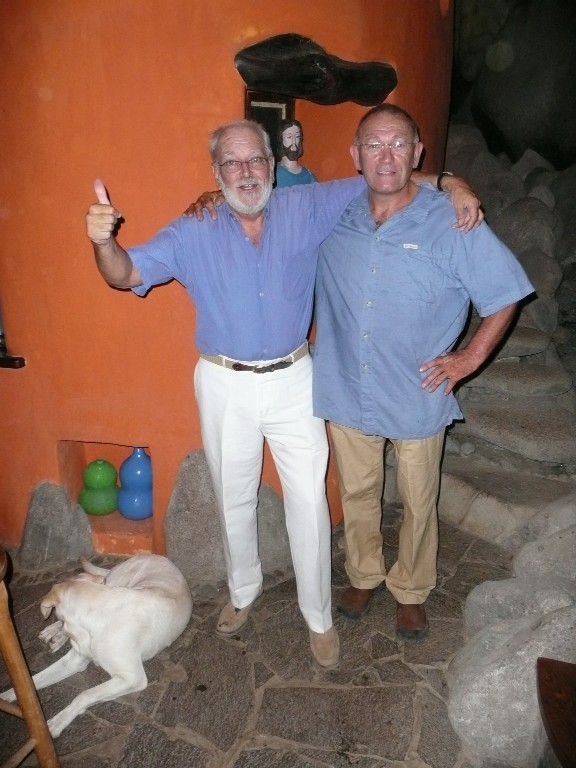

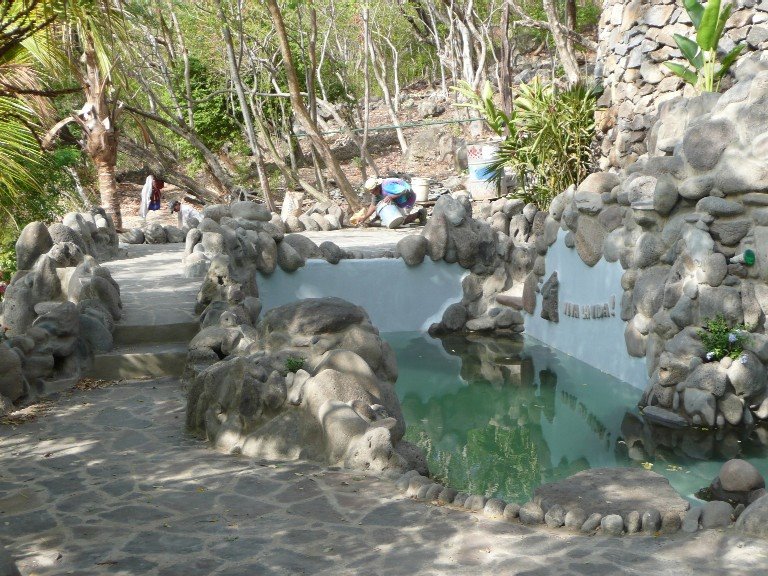

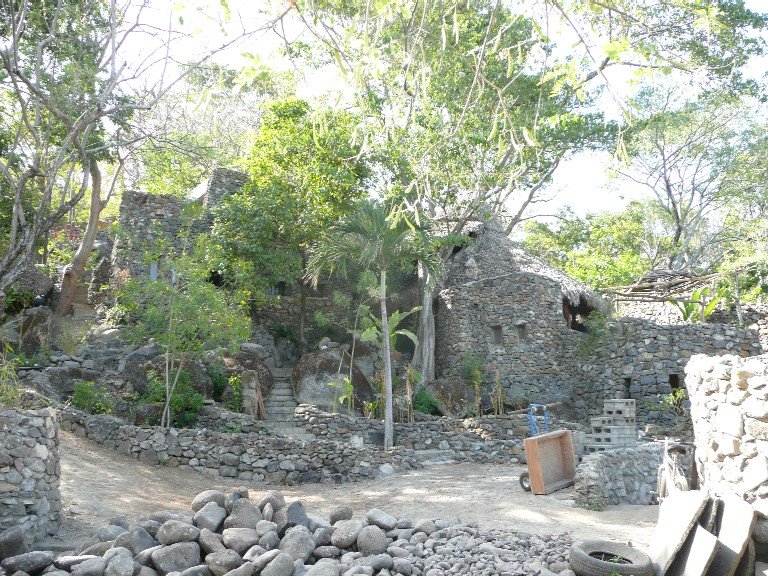

Throughout my three weeks in the States, Pat has been here, where I am now, in Laguna de Apoyo, helping out a new friend with his building project. It was supposed to be ten days, but as we enter the fourth week, he is starting to get a bit antsy, the time remaining to work on our own house eking away. Nevertheless, this is an amazing place, constructed from stone and concrete, the work of an architect with an unlimited imagination. I'll put in a couple pictures, but they don't do it justice. We hope to head home by the weekend, and resume some sort of "normal" life, get the house further along, and enjoy the two months remaining to us here.

Friday, April 25, 2008

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)