Time is running out. Three weeks left, and much to do. We finally managed to locate the Saltillo-style tiles for the floors, purchased them, and had them delivered (well, as far as Edwin's place. Then two very full pickup trips out to our house, brazenly using child labor to load and unload). Pat began prepping the floor yesterday, and the actual laying begins imminently. This is exciting not only because it's our new floor, but also as it represents more or less the only real progress we've managed this trip, other than the well. Pat is optimistic he will also have time to close the place in (it's now open all along the roof-line in typical Nica fashion), which ideally will keep the place from once again becoming a safe and pleasant harbor for every wee flying beastie in SW Nicaragua, not to mention the scorpions, geckos, spiders, and snakes that also set up residence last time we left. The guy we bought the tiles from, Rodolfo, was a bit of a character. Like the tiles, he comes originally from Ocotal, up in the north, from a once wealthy coffee plantation owning family. Then came the revolution, their lands were redistributed to the local farmers, and he headed off to university in Mexico (the rest of his family moved to Managua). He married a Mexican girl, equally white and wealthy, and now divides his year between the two countries. We noticed a Land Cruiser jeep, identical to ours, parked out back, and Pat asked him about it (he spoke excellent English). Turns out, it's a '77, and he's the original owner. The family also had the Ocotal Toyota dealership for many years, and he still has the shop manuals for every vehicle made up to the late 80's. He showed us a picture of a very 70's-looking young man, curly dark hair and droopy mustache, leaning against the hood, holding an AK-47. Yep, Rodolfo, age 17, a few months before heading off to Mexico. Later on, the Jeep went missing, and friends reported seeing it driven by soldiers from the National Army (enemies of the Sandinistas) toward Honduras. His mother went up there, found the jeep, slipped inside, and drove it home, where it sat out the rest of the civil war under a mound of tarps. Exciting stuff.

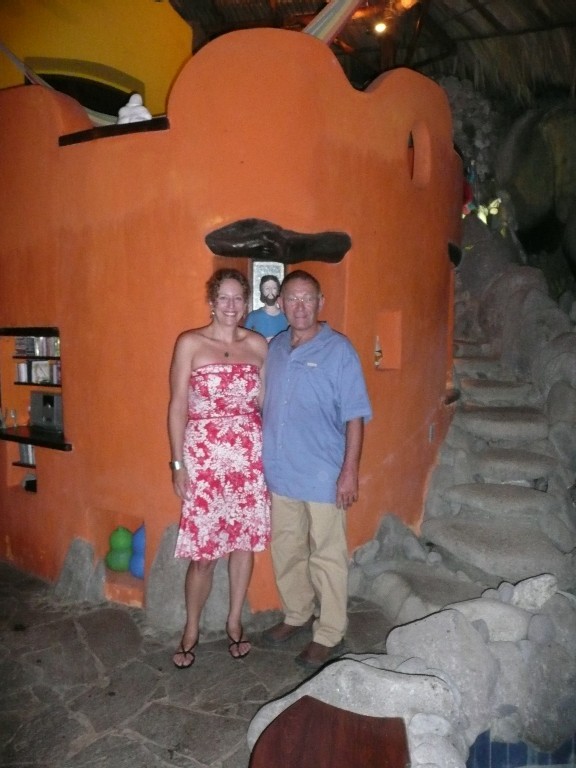

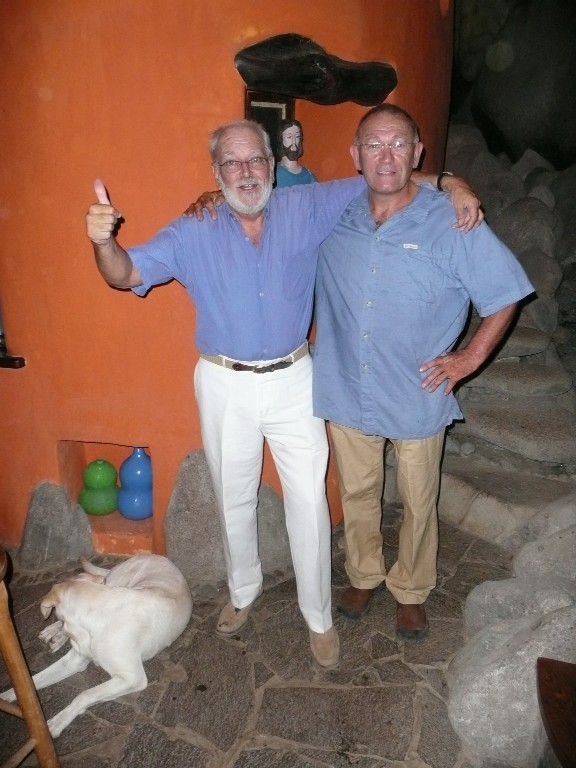

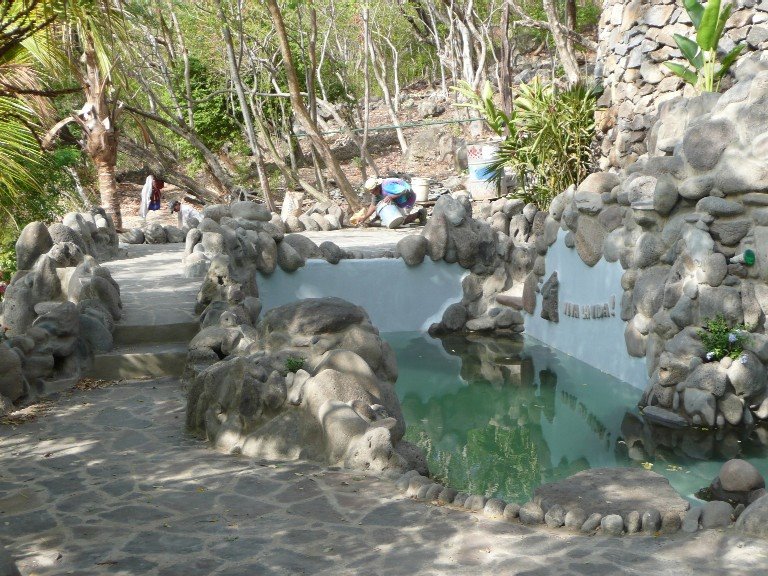

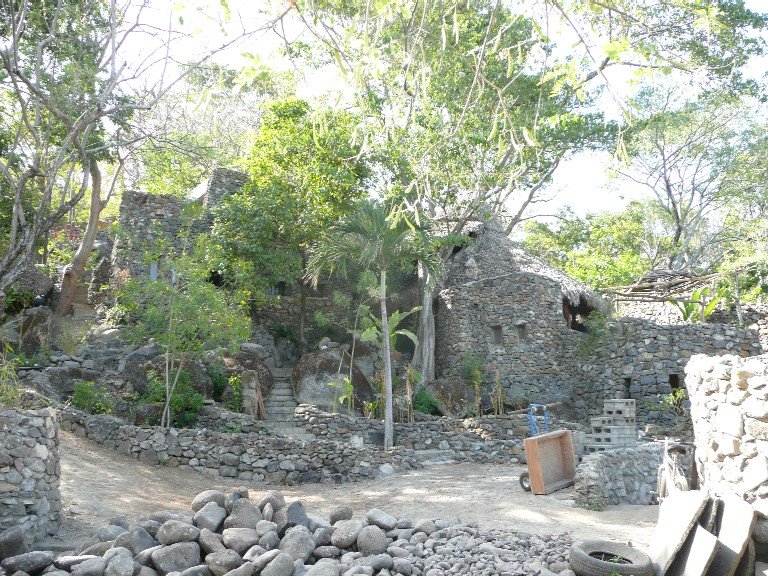

We went back up to the Laguna a last time to attend Etienne's fiesta. It seemed to go off as he'd hoped, with all the Harvard grads (it was a 40 yr. reunion) suitably impressed, happily sipping their drinks and lolling about in the pool. I met a few interesting people, including a woman called Geralyn who is down here working for Opportunities International. This is a 35 year+ org. similar to Kiva, and based on the Yunis principle of small loans, primarily to women. They are branching out a bit, however, and planning to start building high schools in rural areas, utilizing a sort of voc-ed, hands-on, real-life applicable model, and have selected Rivas as their first location. I immediately began advocating for Buenos Aires, as we have schools only to the 8th grade, and she agreed to come down and take a look. They want to emphasize agriculture and tourism, the two strengths of this part of the country. We'll see where it all goes, but it definitely looks like a project we could get involved in, one way or another.

Back down here in Rivas, we had the chance observe the mind-boggling inefficiency of the Rivas hospital first hand, after a kid slammed into the jeep on a bike. We were just trundling through town on a main road, at maybe 20 mph in rush hour traffic, when a blur through Pat's side window caught my attention. Before I could say anything, the blur transformed itself into a bicycle, flying out of a side street and completely refraining from either turning or stopping, choosing instead to plow directly into our left front bumper. There was the proverbial 'sickening thud', followed by the sight of the boy flying off the bike and landing just in front of the now frozen jeep. We both leapt out, hearts in mouths, to find the boy—now more clearly visible as a young man (he turned out to be 18) slowly getting up and limping to the curb. In just a few seconds a large crowd had gathered, and to my relief, several of them, who must have witnessed the whole thing, began berating the kid, asking him what the hell he'd been thinking, etc. Pat palpated his arms and legs, ascertaining nothing was broken, but concerns about internal injuries impelled us to take him to the hospital (where, it should be noted, he did NOT want to go, and only grudgingly agreed to accompany us at the urging of his friend and several bystanders). As we were pulling away, a pedal taxi went by and yelled, "Lucky bastard—now you'll get some money!" causing the kid to blush furiously, much to his credit. Anyway, we arrived at the hospital at 5:15pm, and while there were a few people milling about the waiting area, and we could make out sounds and movements through the curtains covering the glass doors to the examination area, it was a full 30 minutes before an old woman shuffled out and asked the boy if he had his admittance papers. When he said no, she said, "Oh, well, without them, you'll be here all day and night!" to which I replied, "No one has been out here to take his information—could you please find someone?" She stared at me for a minute with an expression much like mine would have been had the dying plant in the corner suddenly proposed the idea, then nodded and shuffled back inside. Another half hour went by. Finally a younger woman came out and beckoned him over. On what appeared to be a piece of scrap paper, she jotted down his name, address, age, and complaint (he said he's fallen off his bike) with a pencil stub, then told him to go inside and wait. In the 45 minutes that followed, I chatted with his friend, who'd been riding behind him, and who happily told me he had neither brakes nor particularly advanced riding skills. "He's always getting into accidents!" This statement was later borne out when we eventually pulled up to his house and just before we stopped, the boy, Juan, leaned forward and in a panicky whisper, pleaded with us not to say anything about anything to his mother, please!

Someone in a white coat pronounced him bruised but otherwise undamaged, and gave him four or five prescriptions for assorted painkillers and antibiotics. We filled them for him—I think it came to just over $3 for everything--then drove him home. Imagining how much worse it all could have been kept us preoccupied for days…even after various Nica friends told us it was Juan who had been lucky...apparently if we had been Nicas, we'd have gotten out, ascertained that he wasn't dead or severely injured, yelled at him for being careless, and driven off into the sunset, no doubt complaining loudly about being inconvenienced by riff raff.

Oh, the fuel strike has been "resolved", though I use the term loosely. From what I can understand, the Ortega government agreed to a price reduction of $1.30/gal. for diesel, and around $. 45/gal. for gas, but only for licensed public transportation drivers, such as busses and certain taxis. To offset the loss, fuel prices for the rest of the population have been steadily increasing all week, roughly $.05/day, so that as I write, a gallon of diesel is going for approximately $6.15/gal. and climbing. As you might imagine, people are not happy about this, and for the first time, we have been seeing the formerly unimaginable: posters of Daniel (Ortega) are starting to be vandalized. We passed one the other day on which was scrawled "Ignorant Dictator", and yet others in Granada where his face had been blacked out. All of this has made it increasingly difficult for all the Sandinista mayors, many of whom are up for re-election this fall, to campaign effectively. It may take more than free pink hats this time…last week in Buenos Aires, the local candidate gave away an entire bicycle!

Speaking of fuel, we had our own close encounter—with a kerosene-based mixture used by the city to fumigate before and during every rainy season. Basically, a guy in a GhostBusters get up, trudging from house to house and blasting this acrid poison into every nook and cranny. We had our first experience last spring, early one morning, still half-asleep, when we heard voices, and before we had time to react, our bedroom door burst open and we were coated with a blast of slick smoky spray. Pat yelled, I dove under the sheet, the door slammed shut, and we were left there wondering what the f**k just happened. At least this year, we were up and about, so when he showed up, we asked him not to spray our room. He did the rest of the house, resulting in a surprising number of melodramatic cockroach deaths throughout the morning, but no apparent reduction in either mosquitoes or ants, our two main pests.

Finally, a run-in with a bent traffic cop illustrated how far we've come, both in terms of experience and language acquisition, since our first experience soon after our arrival back in Feb. '07. We were waiting to turn left at a T-junction about 40 miles N. of Rivas, when Pat spotted a cop across the way. At first he just glanced at us and looked away, but as a line of cars forced us to wait to make our turn, he glanced again and this time realized we were not quite locals. Pat said, "He's going to wave us over." And sure enough, as we pulled out to turn, the little day-glo baton began twitching, and we slowed to a stop on the shoulder. He asked for our documents, now kept in a small Ziploc baggy against dust and moisture, and after a cursory glance, began telling us we didn't have the right circulation card for our plates. Well yeah, we know that, there are no plates available in Nicaragua at the moment, so every 90 days I have to go stand in line at the transportation desk in the Rivas Police Station so they can stamp this temporary circulation and tell me to be patient a while longer. Since being pulled over for document checks is a frequent affair here, we've shown this paper to probably a dozen cops, every one of whom has wished us a nice trip and sent us on our way. Until now. So he starts getting out his book as if to write us up, and Pat gets angry, which makes the cop angry, so I get out asking him to show me what exactly is wrong with our plates, and he starts again about us needing the green card, and I launch into a polite but firm explanation of our situation, pointing out that we received the temporary card from a cop just like him, and that we've shown it to many other cops, just like him, and we are certain everything is in order, but if he has a problem, maybe we could call the police station, and if he just wants to give me his name…We're free to go? Why, thank you, sir. ¡Tenga un buen dia!

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

No comments:

Post a Comment